Opmerking: Deze blog is vanaf nu officieel tweetalig! Er zullen zowel Engelstalige als Nederlandstalige artikels verschijnen.

Monday morning, the footballing world woke up to the nightmare of many football fans. 12 of the major footballing teams in Europe, and therefore the world, announced they are forming their own football league, the European Super League (ESL). Unlike the current Champions League, the ESL gives these 12 Founding Members (yes, they are pretentious enough to call themselves that, with capital letters intact) a permanent position in the league, with other teams scrambling to get invited by the benevolent giants.

This announcement was met with a lot of critique by existing footballing leagues, such as UEFA, Fifa, and the national leagues, who stand to lose with the new arrangement. Their concerns are echoed by footballing legends and fans alike. They point out that the ESL goes against the competitive spirit of sports and that it does not respect and take care of the footballing pyramid that is essential to the survival of football. In the end, footballing clubs encountered more resistance than they expected and revoked their decision.

But we should not be blind to the harsh reality of modern football, something which every fan knows and denounces, but stands powerless against: the beautiful game is no more. The pyramid that everyone is referring to has been under attack and destroyed one step at a time over the last decades. The ESL is merely the logical conclusion of a long process of capitalist enclosure of football.

Capitalism and Football: One Cannot Live Without The Other

Many people are aware that the history of modern football starts in England (remember that annoying ‘It’s coming home’ meme during the World Cup in 2018? It has something to do with that). But not many people realise the strong historical link between capitalism and modern football.

Sports that are similar to football were already being played throughout the Middle Ages in England (and already before in many parts of the world). But these games were without formal rules and would sometimes cause severe injuries and death.

The enclosure of public land by rich elites forced peasants to move to cities and work as wage labourers, which enabled the Industrial Revolution. But large gatherings of people in factories, pubs and churces made workers able to play football together on an unprecedented scale. It is for this reason that a lot of the early football teams (often still existing today) were clubs made up by the working class. But the violent nature of the sport, focusing on physical dominance, was strongly disencouraged by capitalist employers, because workers would often end up injured and unable to work.

The sport was also very popular in schools such as Eton and Cambridge. Again, the violent nature was not deemed appropriate in the Victorian Era, which was focused on rules, control and civility. Therefore, in the 1850’s and 60’s, footbal became regulated, with stricter rules and regulations that saw sports as a way to build virtuous Catholic men of the artistocracy. As Britain was the strongest imperial power of that time, these young men would take their sport with them abroad, thereby globalising the game. And thus from its very inception, football was conditioned by the economic and social conditions in which it emerged, with elites attempting (and succeeding) to control the rules of the game.

Football For Profit: Neoliberalism In Action

From the end of the 19th century, football would go on to reach enormous successes. It spread from England to other parts of the world, where local communities would adapt it to their culture and style. Many clubs, footballing organisations and tournaments were formed in the first half of the 20th century. But despite the popularity of the game, football was not yet the big business it is today.

In the 1980’s, a new ideology came of age in the West. It is the ideology of free markets, free movement of capital and privatisation of public goods in pursuit of never-ending profits. Neoliberalism changed the way football was seen. Before, football was strongly tied to local identities, and investment into football clubs was motivated by a sense of pride, status and custodianship. Profit was not a motive for investment; indeed, it was even illegal for directors to receive profits from their clubs. But when Tottenham used a legal loophole to circumvent this rule and put the club on the stock market, many other clubs followed. Sporting considerations were now subject to the maximalisation of shareholder value.

Arguably the biggest catalyst of football becoming a business, however, were the television revenues. Almost every family in the West posessed a TV, and interest for football was booming. The deregulation of media allowed the shift from football being free on TV to football being accessible exclusively through expensive subscriptions. Fans’ status shifted from ‘cultural citizens’ to ‘entertainment consumers’. The increased demand for football on TV, combined with expensive subscriptions, allowed the television revenues to rise exponentially from the ‘80’s onwards.

Club owners recognised this trend and wanted a bigger piece of the pie. In England, this was most notable with the break-away in 1992 of the 22 largest clubs in England from the English Football League, which had started in 1888. These clubs cut an exclusive lucrative deal with the TV company BSkyB, owned by Rupert Murdoch.

A similar thing happened on the European level. The European Cup, which was established in 1955, allowed the champion of every national European league to enter the tournament, where a team would compete in knock-out stages to reach the finals. But the wealthy teams and leagues were dissatisfied as only one team per country could enter, and the knock-out stage did not guarantee large and stable income streams to the clubs. Furthermore, a more extensive tournament could increase TV revenues. UEFA reformed the European Cup in 1993, rebranding it as the Champions League and allowing more teams to participate. However, the big clubs still were not satisfied, and in cooperation with JP Morgan and media moguls such as Murdoch and Berlusconi, threatened to form their own break-out league (this theme should sound familiar at this point). UEFA further reformed the Champions League in the subsequent years to guarantee the participation of the big clubs.

There are three consequences to these evolutions. First, the television contracts encourage further commodification and profit-seeking in football. This is most apparent in the sponsorship deals with companies, whose names and advertisements now appear on jerseys and on the sides of the pitch.

Second, inequality became deeply entrenched into the football system, both within and between leagues. Spain, Italy, England and Germany are the richest football leagues. As a consequence, European success (or even participation in the final knock-out stages) is increasingly only attainable for clubs from those countries. But even within leagues, inequality is rising. Smaller clubs are increasingly forced into bankruptcy, lacking amounts that bigger clubs spend on a Monday. In England, the combined revenues of Manchester United, Manchester City, Spurs, Chelsea, Arsenal, and Liverpool as almost exactly equal to those of the other eighty-six clubs in the top four divisions put together.

Third, it cemented the rise of football clubs as transnational companies. Whereas clubs used to be dependent on their immediate surroundings for financing, television revenues detached clubs from their place. To maximise their profit, they don’t focus on the thousands of fans in their home town, but on the billions of people on this planet that they can market their brand and sell their merchandise to. Combined with the increased transnational, private ownership of clubs, football clubs have now truly become transnational companies. They are no longer one single entity but form a complex legal web of businesses and subsidiaries with one goal only: to make a profit.

In turn, this has led to football results on the pitch barely impacting financial income. One could be forgiven to think that Manchester United have been struggling since the departure of legendary coach Alex Ferguson. After all, they have not won the Premier League or Champions League even once since then, and has Paul Pogba really ever looked like he truly belonged? But, all of this is beside the point. Despite the meager footballing results, United’s revenues have doubled and they are the third richest club in the world. From the owners’ perspective, Manchester United is a success story.

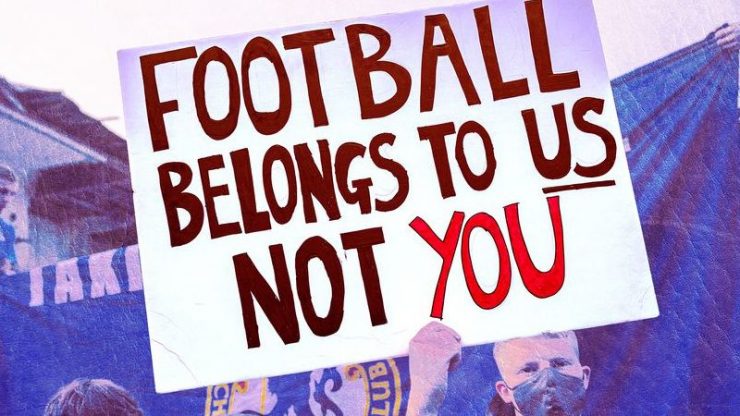

The conversion of football clubs into transnational companies decreases the accountability to the fans. It explains the enormous frustration of for example Arsenal fans, who have protested rising ticket prises and a lack of success on the pitch, but have simultaneously witnessed the first sponsorship deal with a national government (Rwanda). Arsenal is just one example, but countless protests and conflicts have occured between owners, who see the club as their personal investment project expecting profits, and fans, who desire accessible and enjoyable football.

The European Super League: Late-Stage Capitalism?

The announcement of a European Super League should therefore not come as a surprise. The excellent report by Goal on Andrea Agnelli, the president of Juventus and Vice-President of the ESL, clearly unveils the visions of Europe’s club owners. The goal is to create guaranteed revenue streams, detached from football results. This requires abolishing uncertainty and competition, and increasing inequality between clubs. Small clubs, after all, should not be able to threaten the income stream of bigger clubs just because they won.

Capitalism is a system that claims to promote competition, while in reality it eliminates competition to maximise profits. It encloses public goods and sells them for a profit margin. And importantly, in doing so, it risks devouring the very value it seeks to capture. Nowhere is this clearer than sports. The European Super League is the logical conclusion of a long historical process of capitalist enclosure. However, what they do not understand, is that the enclosure destroys the value of the sport they seek to capture.

Whether the European Super League goes ahead or not is ultimately not the question. If it does not succeed now, it will at a later point, one way or another. Such is the nature of the beast. The question, therefore, is whether we are able to imagine a new football world, that redistributes wealth, puts fans and communities at the centre and ownership under democratic control. The answer, my fellow fans, may end up saving the beautiful game.

Published by